Jumpstart the Imagination…

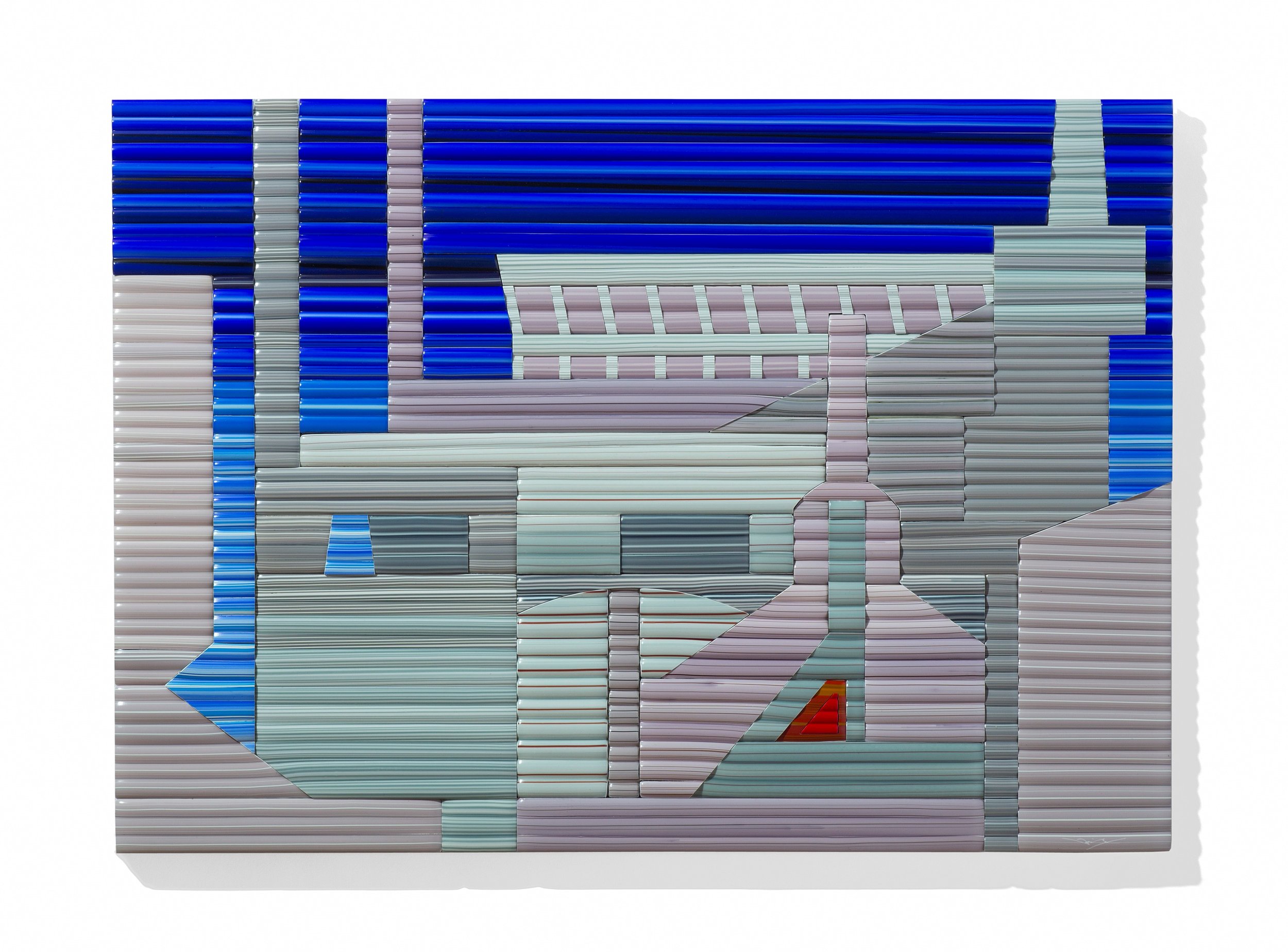

Perspective, 2011,

Individual series

Blown glass, sandblasted and acid polished, anodized iron, 13 3/4 x 22 x 14” photo: Bill Truslow

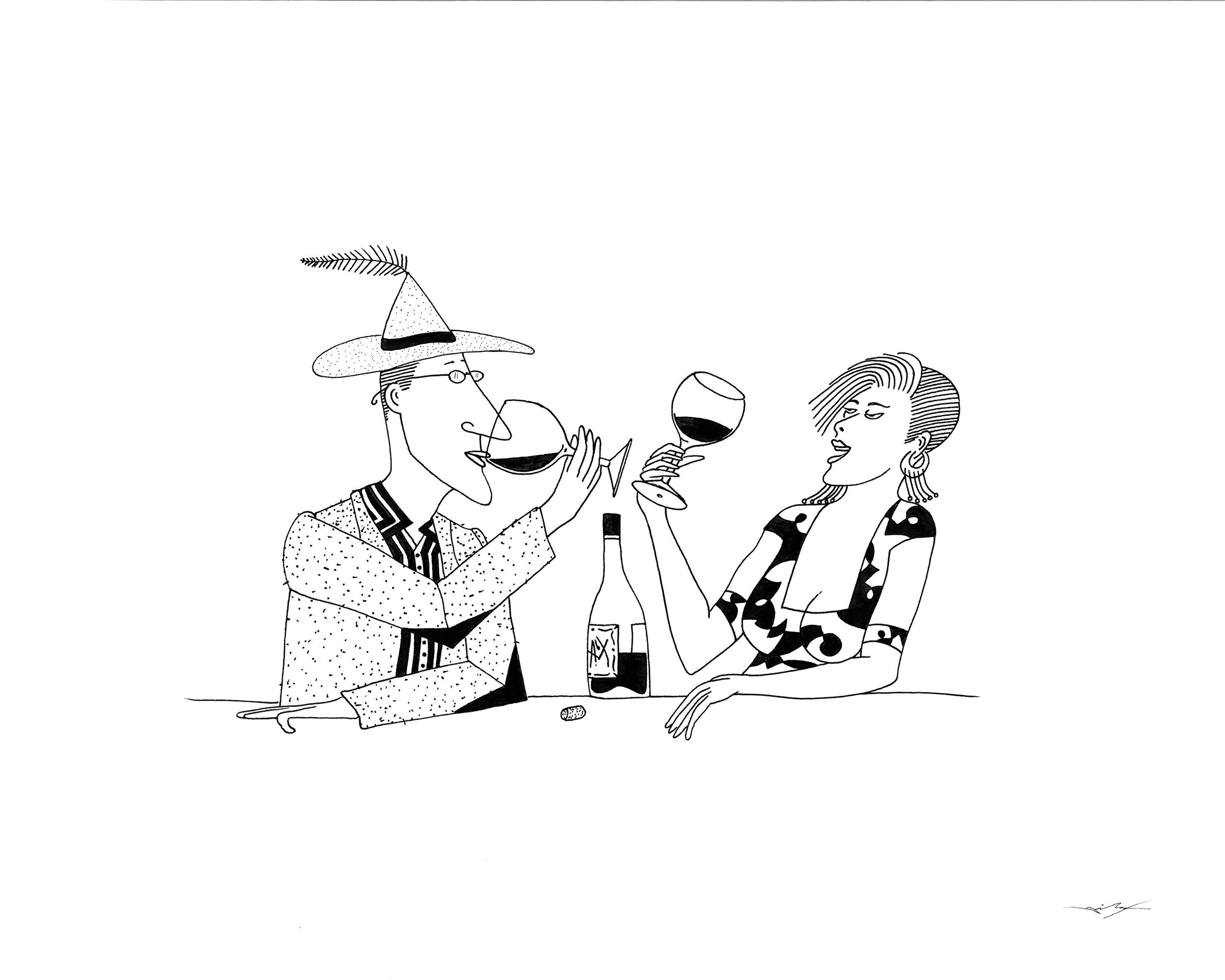

Dan Dailey never suffers from a shortage of ideas. His sketchbook is full of them and he’ll never get to all of them, even after 50 years making art. Often it begins with a word. The word could be “dubious” or “soft,” “perspective” or “chill”. The word triggers an image. Dailey is an object maker, intrigued and inspired by how an object can be a physical manifestation of a concept. The English language has roughly 1,000,000 words in it. That’s a lot of potential ideas.

His penchant for working in series—Circus Vases, Abstract Heads, Individuals, and Animal Vases, just to name a few—stems from a restlessness to focus on and develop all the various ideas in his head. When he brings an idea to life, he does so with purpose and empathy, communicating an often quite specific feeling or thought. He is less motivated by technique—by pushing the glass to its physical limits—than some of his colleagues. For Dailey, fine craftsmanship is for lending credibility to the object. He is not motivated by making a thing of beauty, although he achieves an undeniable elegance anyway. For Dailey, form is a vehicle for narrative. He knows this approach makes him unique among glass artists, and as he has gotten older, he has gained greater perspective and gratitude for the fact that people seem to like it.

Covid provided a rare period of reflection on his career that Dailey’s busy schedule never allowed. He has not been on a plane since February 2020, but before that he traveled back and forth to Seattle three or four times a year and regularly worked in Italy and France. Halted work and travel meant more time to meditate on the past. Add to that, the Columbus Museum has been organizing a traveling retrospective on his work for the past six years that should come to fruition soon, forcing him into a literal and figurative opening of the archive. The curator, Annegreth Nill, came for two one-week visits, and they got all kinds of work out of storage. About 60 percent of the exhibition will come from Dailey’s personal collection (of the approximately 3000 pieces he has made throughout his career, he only retained about 300); the rest will come from private lenders and museums. One piece she chose was an unfinished large circus piece, so some of the Covid lockdown has been dedicated to building its bronze and brass components and casting its patte de verre elements.

A short video about Dan’s design process.

Dailey’s attachment to his earliest work (like from when he was a student) is mostly sentimental, and he values it more for the experience of making it and how that experience developed his art than for its aesthetics. But ever since he established himself as an artist, he has been dedicated to doing things well and making work with lasting quality. He is not fooled by the hierarchy of the new—even though he loves to explore new territories and messages. As this collection at Schantz demonstrates, with work going back to the 1990s, Dailey’s craftsmanship and artistry has been considerable and consistent.

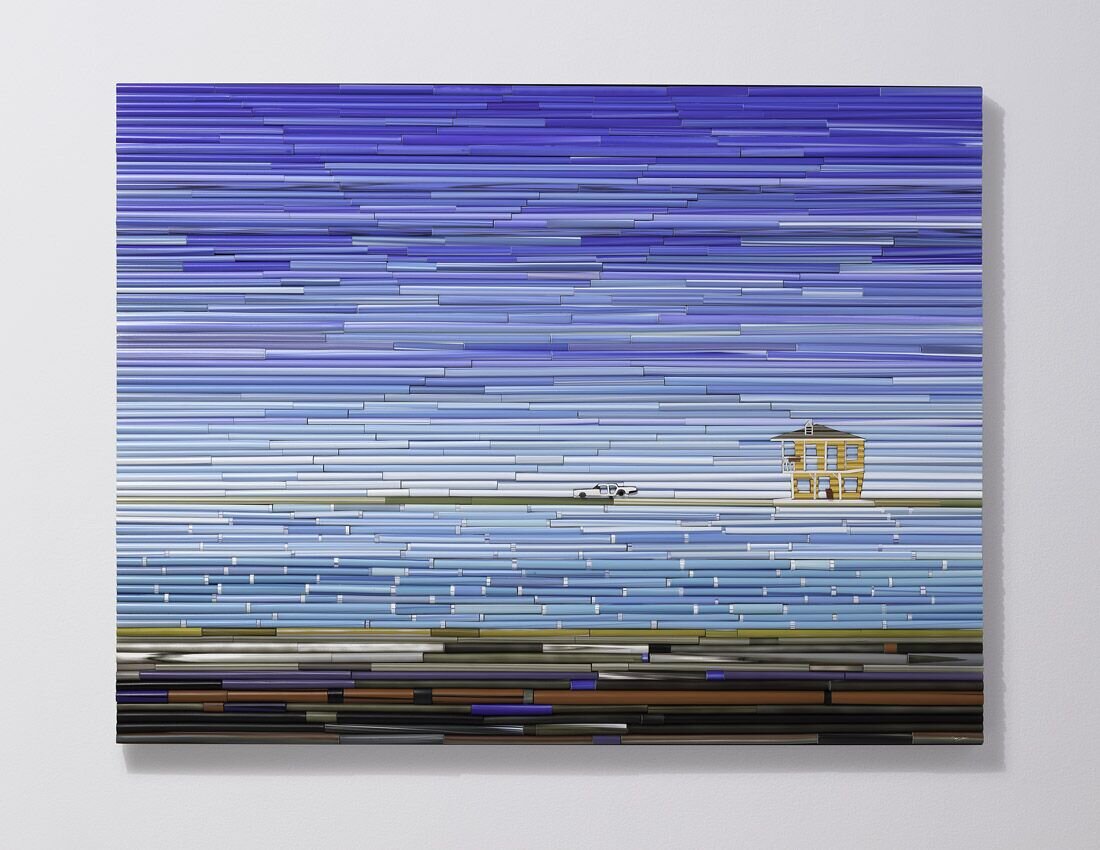

Cupids, 2017. Glass cane, anodized aluminum, 37 x 48 x 2”

When the pandemic hit, Dailey made the necessary adjustments to his staff and his working methods to protect everyone’s health and safety. Many of his assistants, like his metalsmith, Dana, and his son, Owen, who does all the glass casting, have their own studios. There was an initial sense of disorientation when everyone retreated to their own spaces, but eventually they learned to use this to their advantage and work was able to continue. Right now, he is working on a pair of sconces of two beret-wearing artists for a client in Chicago who loves photography, and with whom Dailey had numerous conversations about Cartier Bresson. He is also working on a cane mural commission that will eventually go to Florida, an interesting graphic exercise in linear abstraction. In years past, Dailey would go to Seattle to blow glass, working at Ben Moore’s studio with Dante Marioni and Richard Royal, but since Moore passed away in the summer of 2021 the studio has been closed, and for various reasons Dailey hasn’t felt ready to either travel or start up a new series of work just yet.

Likewise, 2013. Vitrolite, nickel and gold plated brass, anodized aluminum, various glass details, enamel paint, 31 x 44 x 6”

During the forced restrictions, Dailey learned to slow down a little, rethink the way he approaches the production of his pieces, and indulge in some other passions. One of those passions is cars, which Dailey values as a ubiquitous part of American culture. Recently, he was invited to exhibit automobile art at a car show in Las Vegas, and even though he has done glass vases and Vitrolite murals dedicated to the subject he is taking a new tack by working some Andy Warhol-style silkscreens. Dailey’s studies of cars—both in glass and in print—are less about the cars themselves and more character explorations of the drivers. Dailey is fascinated by what he calls “the automobile ego,” especially prevalent in LA where people are defined by their cars. That said, he loves to buy cars in LA because they are usually well-kept machines with low mileage whose owners keep them briefly then sell them for the next big thing. Over the years you might have seen Dailey driving one of his Saabs, his 1980s Mercedes, or his prized ’55 Thunderbird.

If driving is a big part of Dailey’s life (he has kept his Covid travels to within several hundred, drivable miles of his New England home), reading has also always been a valuable diversion. Dailey wakes up around 5:30 in the morning and reads periodicals (by 6:30 he is exercising and by 8:30 he is in the studio). He has subscribed to The New York Review of Books for 30 years. He used to look forward to his six-hour flights across the country or over the ocean, with no obligations or interruptions, in which he could lose himself entirely in a book. These days, finding an hour or two in a chair just reading for pleasure is a challenge, with his many studio projects and the ongoing maintenance of his large, old property. But his recent accomplishments include Hell’s Angels by Hunter Thompson, The Tyranny of Merit by Michael Sandel, American Nations by Colin Woodard, Tom and Jack by Henry Adams, A Little History of the World by E.H. Gombrich, and Five Points by Tyler Abinder. He’s still working on When Christians Were Jews by Paula Fredrikson and American Nations by Jill Lapore, which like textbooks he can put down and pick up and still easily get back into the flow.

For an artist for whom words, ideas, and questions of the human condition are constant fodder for creativity, it is no surprise that books play such an important role in Dailey’s life. It makes sense that he would immerse himself in them at the start of each day, like a jumpstart for his imagination. With the constant inspiration of new literature, his bottomless sketchbook of ideas to tap, and that lengthy list of words still left in the dictionary, Dailey is not done with his character explorations. Whether in the glass forms he is known for or in some new, as yet unleashed iteration, Dailey will no doubt continue to contribute his unique point of view to the world we all inhabit.

Dailey’s show quality 1955 Ford T-bird

Available Works by the Artist…