To appreciate the relationship between John Kiley and Dante Marioni, Kiley suggests you get in the “way back machine” to when he was a high school student in Seattle and an apprentice chef with a knack for ceramics. He was saving money for a course on lost wax casting at Pilchuck Glass School (he wanted, but was too young, to enroll in glassblowing). When a guy came into his restaurant wearing a Pilchuck shirt, they struck up a conversation. It was Dante Marioni, an established glass artist and Pilchuck teacher who proposed Kiley join him a few days later at Benjamin Moore’s studio to talk glass. But the young and somewhat cavalier Kiley missed the meeting, only realizing later when he arrived at Pilchuck that Marioni was a big deal in glass. Kiley looked Marioni up in the phone book and gave him a call, during which Marioni graciously forgave the missed appointment and invited the kid to his studio.

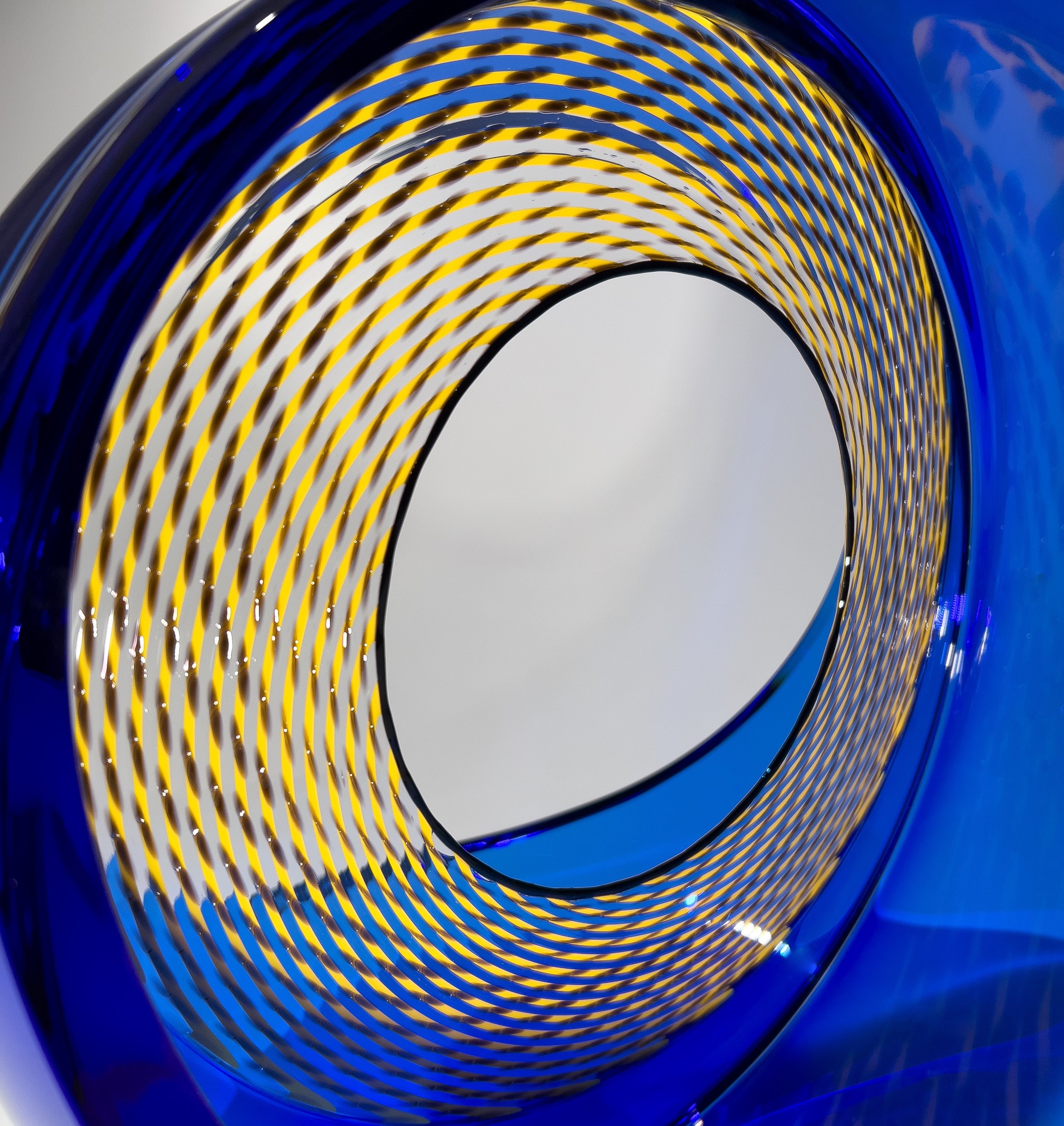

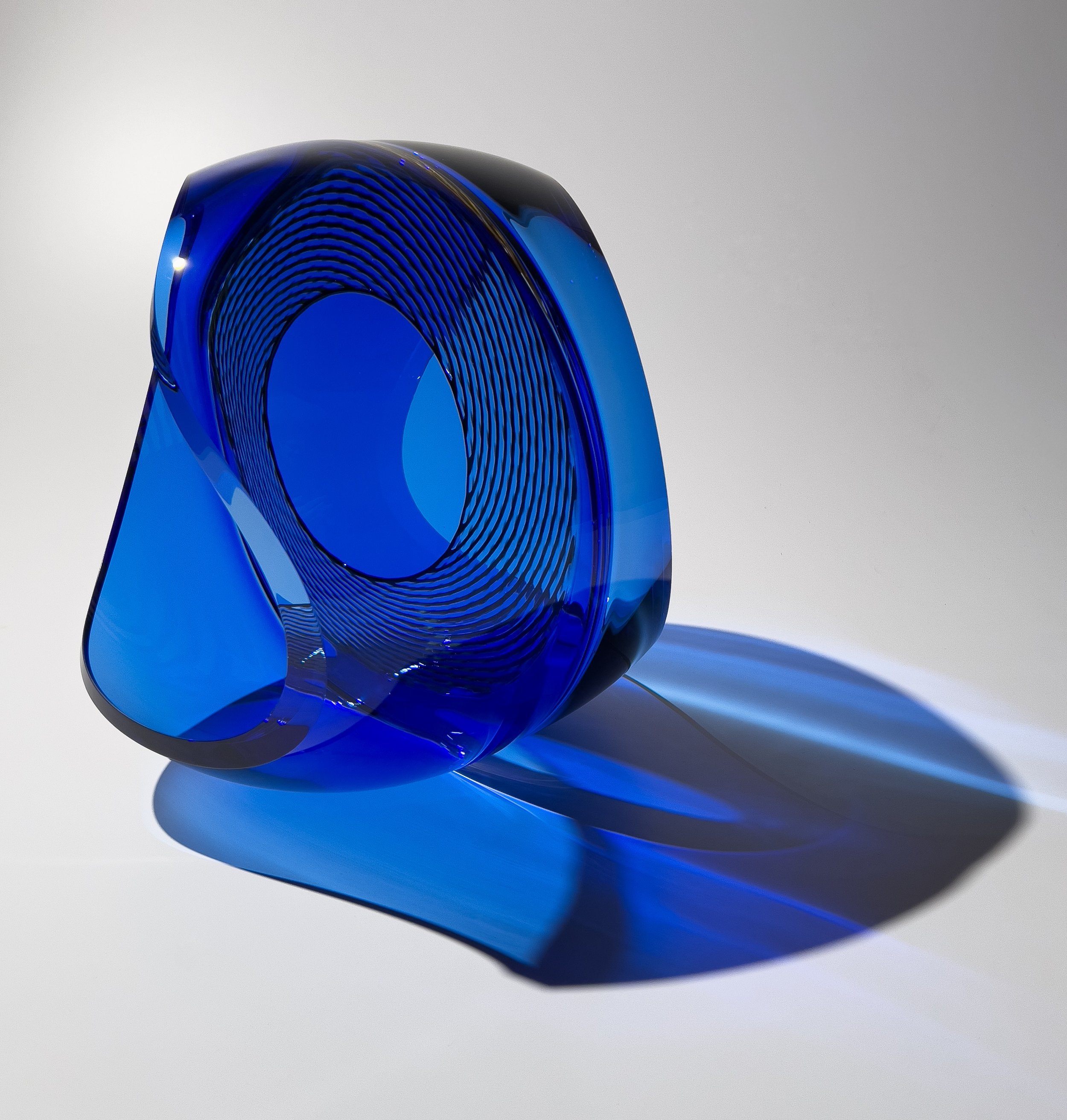

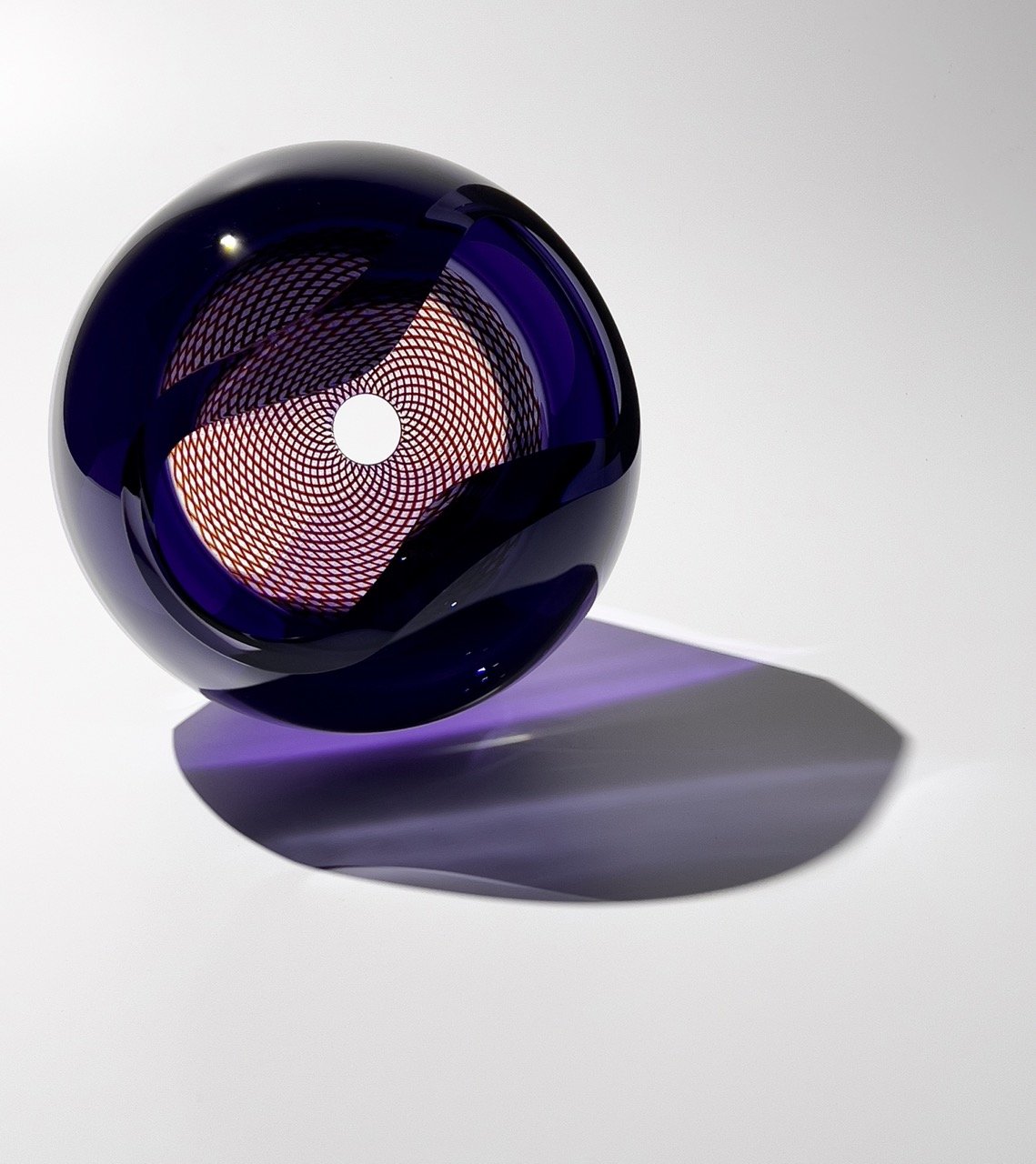

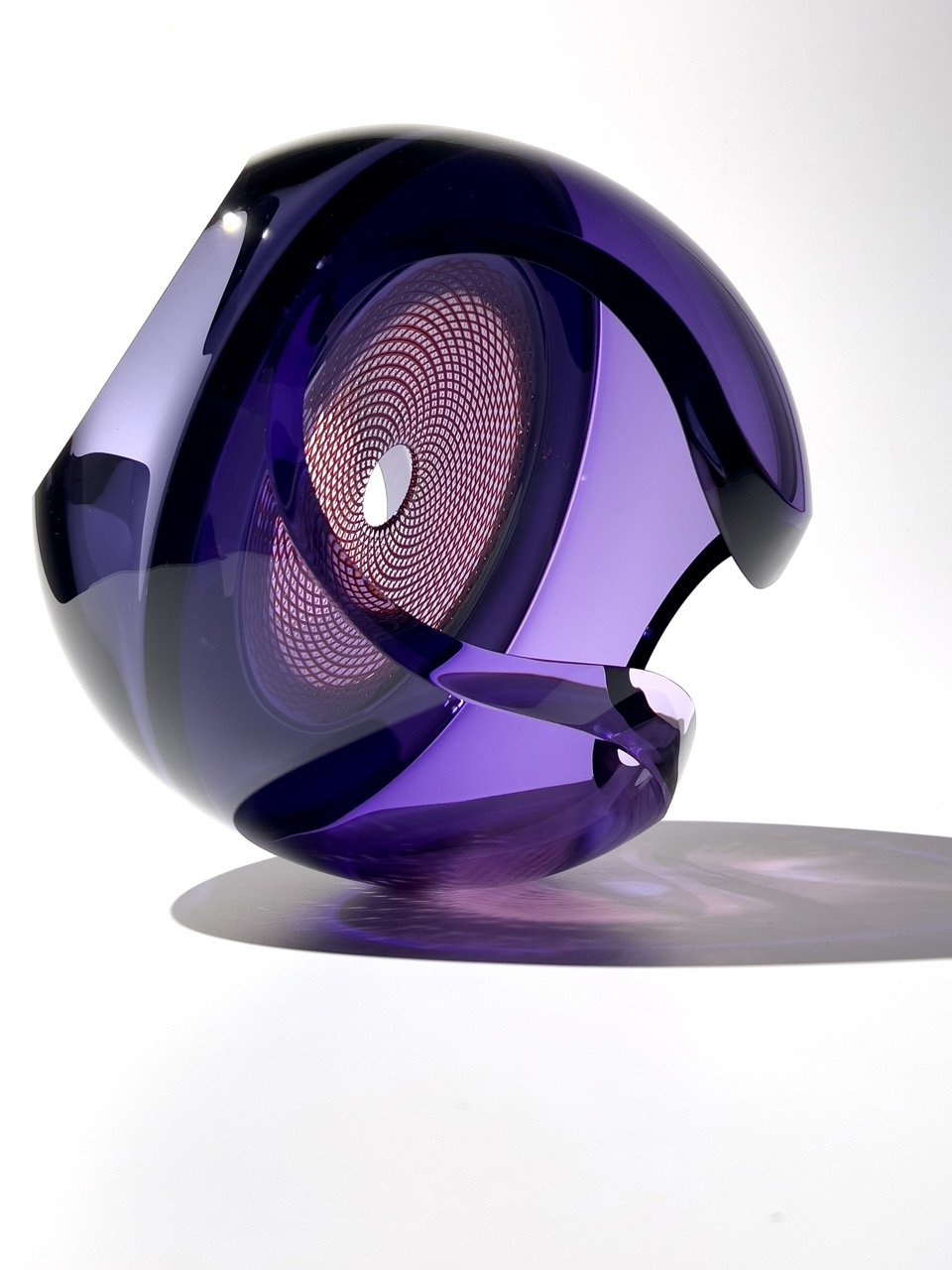

Over the years, the two became colleagues and friends. Marioni recommended Kiley check out the Glass Eye Studio, where the young artist eventually landed his first job in glass. Later, Marioni hired Kiley to his team. Kiley clearly respects Marioni, who was surrounded by glass from a young age (his father is American Studio glass pioneer Paul Marioni), honed classic glassblowing techniques working with Maestro Lino Tagliapietra, then firmly established his own style of elegantly blown diaphanous forms patterned with impeccable reticello cane work. Eventually, Kiley ventured out on his own to pursue his personal style, characterized by a signature technique in which separate hand-blown geometric forms are joined, then cut, polished, and poised in precarious balance; the resulting configurations offer myriad passageways for light and for the interplay of color.

Kiley reminded Marioni that he wanted to work with some of his little “seeds” (kernels of concentrated and painstakingly designed patterns that he blows and stretches in his larger forms), thinking it would be interesting to experiment with a design element as the membranes of his joined pieces. For Kiley’s 2015 Museum of Glass residency, Marioni finally gave him one of these “seeds” to make a piece for auction, though Marioni did not participate in making the work. When Kiley made further requests for more patterns, Marioni—a consummate teacher driven by sharing the craft—encouraged him to learn how to make them for himself. But Kiley is a minimalist by nature, so while Marioni has a passion for perfecting patterns, Kiley chose to focus his glass practice on exploring the essence of the objects. A fortuitous intersection of circumstances finally brought Marioni’s meticulously arranged patterns and Kiley’s joined geometric forms together. In 2017, Kiley’s main projects involved optical glass and a body of work called Fractographs, neither of which could be demonstrated at his forthcoming Museum of Glass residency as they did not involve blowing glass. He figured he would hearken back to “classic Kiley” forms for the week-long stint in the museum’s hot shop. Marioni had shut down his furnace for his annual summer hiatus so he relented when, two days before the residency began, Kiley stopped by his studio and suggested he come along and bring some of his “seeds”. From that residency, and their subsequent sessions together, came an extraordinary amalgam of two minds in joyous equilibrium.

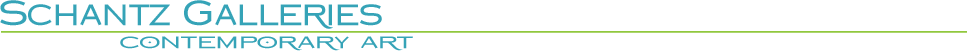

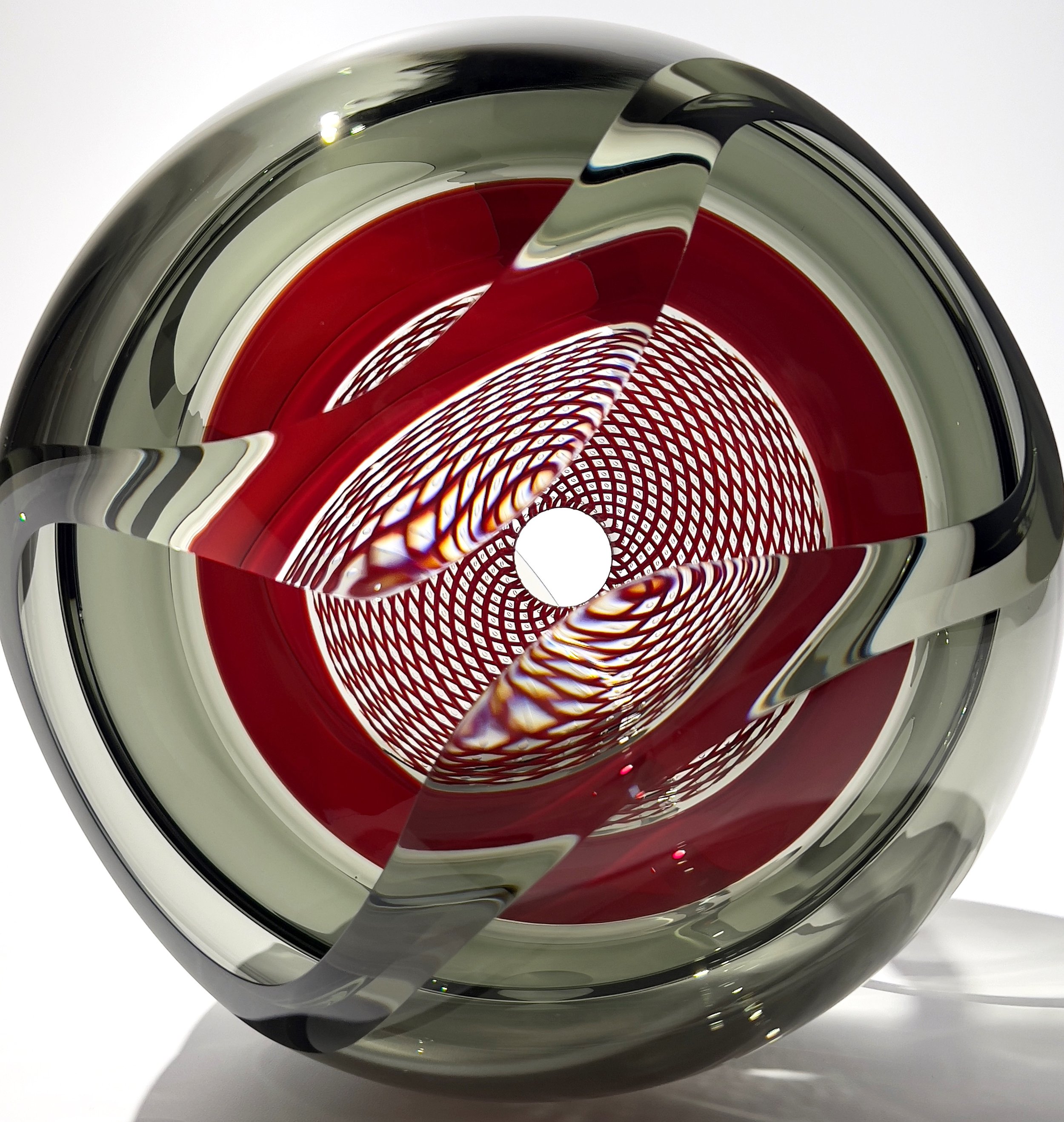

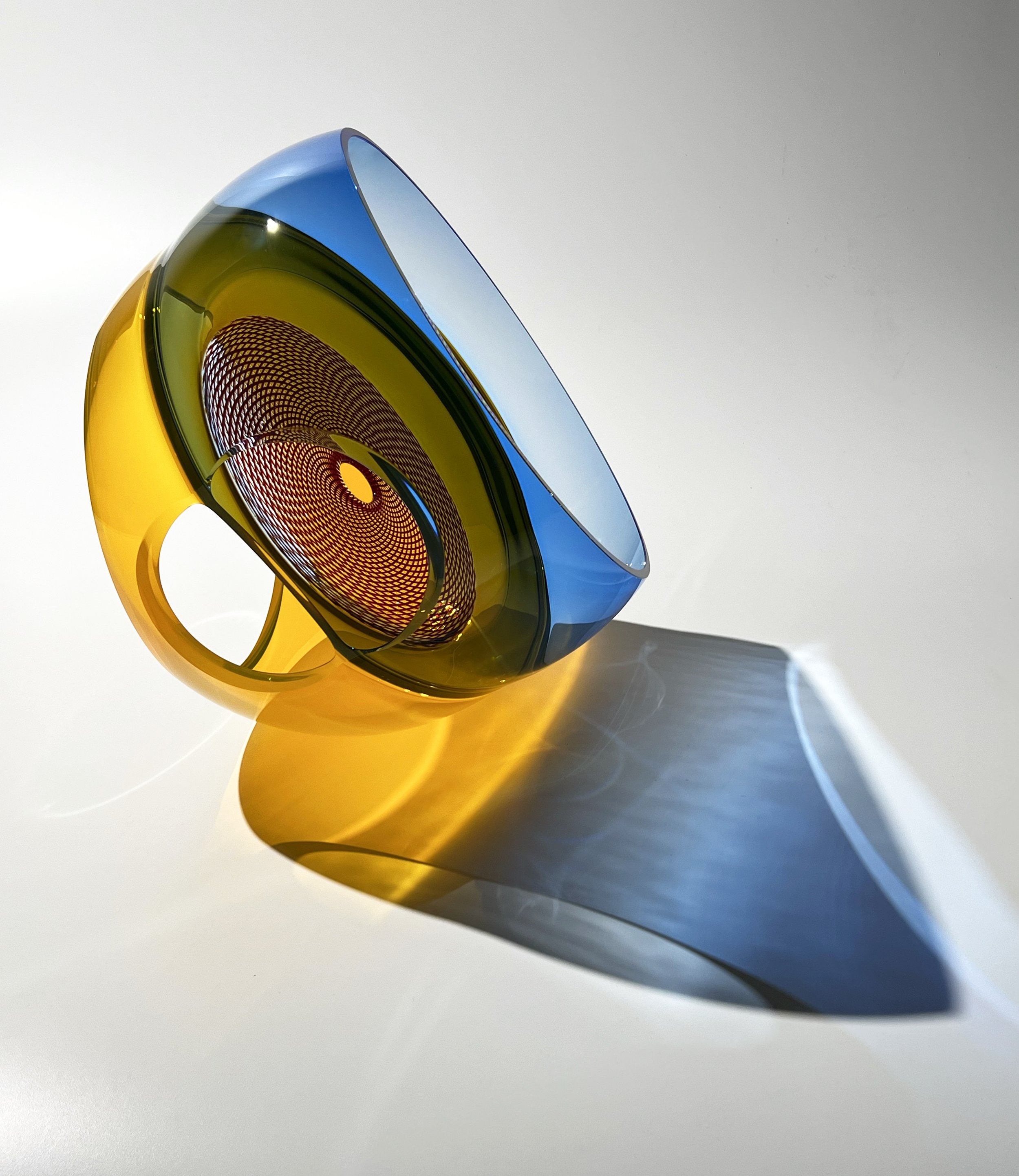

Basket Halo, 2020, 15.5 x 15 x 7"

Each artist is fussy about different things—Kiley rejects work with the smallest bubble (which Marioni finds imperceptible), while Marioni rejects the slightest wrinkle in the reticello (which Kiley sees as beautiful). As the collaboration progressed beyond the Museum of Glass residency, the two worked more deliberately. Whereas in the beginning Marioni would choose the patterns and Kiley would blow, fuse, and cut the pieces, now they collectively and purposely select patterns together and discuss how to cut a piece when it was still a sculptural blank waiting to be formed.

Though Kiley’s glassblowing demands discipline and technical prowess, and each piece of Marioni’s cane represents decades of practice and hours of labor, the physical act of combining Kiley’s two spheres with Marioni’s reticello core occurs in mere seconds. Success is rarely guaranteed. Kiley and Marioni have attempted many pieces that simply did not work, though they have used these failures as lessons and appreciate that accidents can often lead to intention.

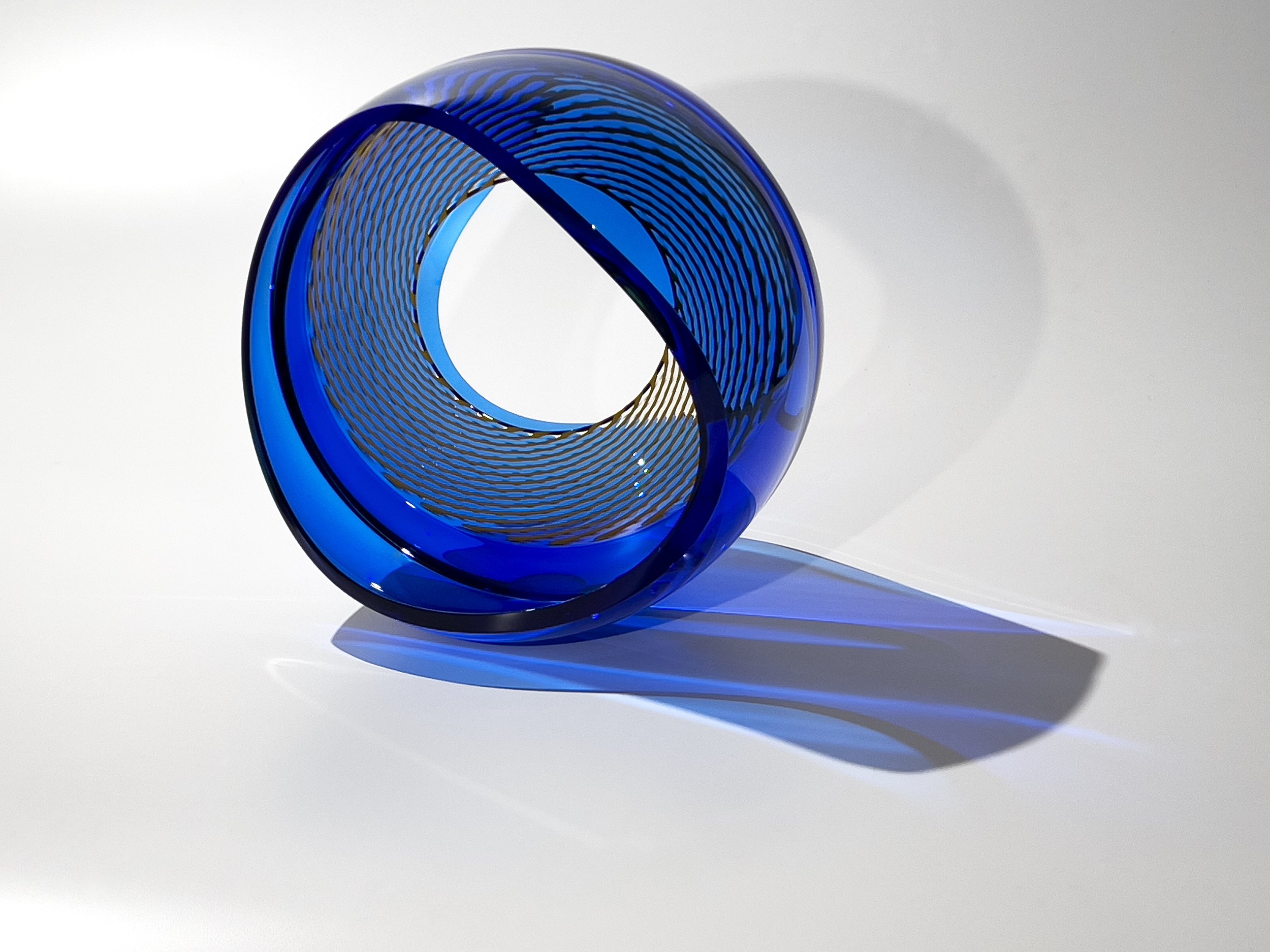

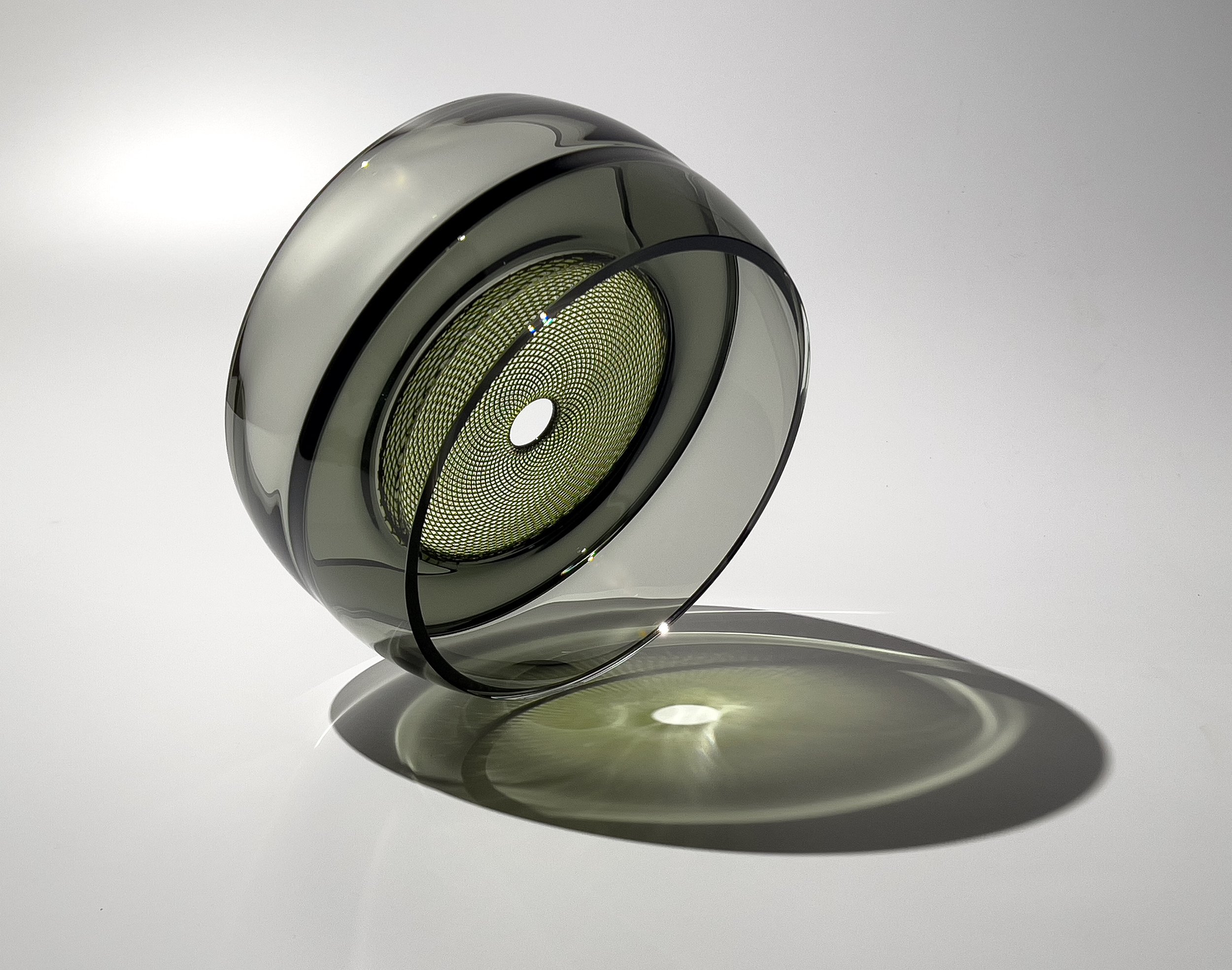

When these two distinct aesthetic points of view coalesce—when Marioni’s fine patterning endows the central membrane where Kiley’s colored objects fuse together—a stunning harmony is achieved.

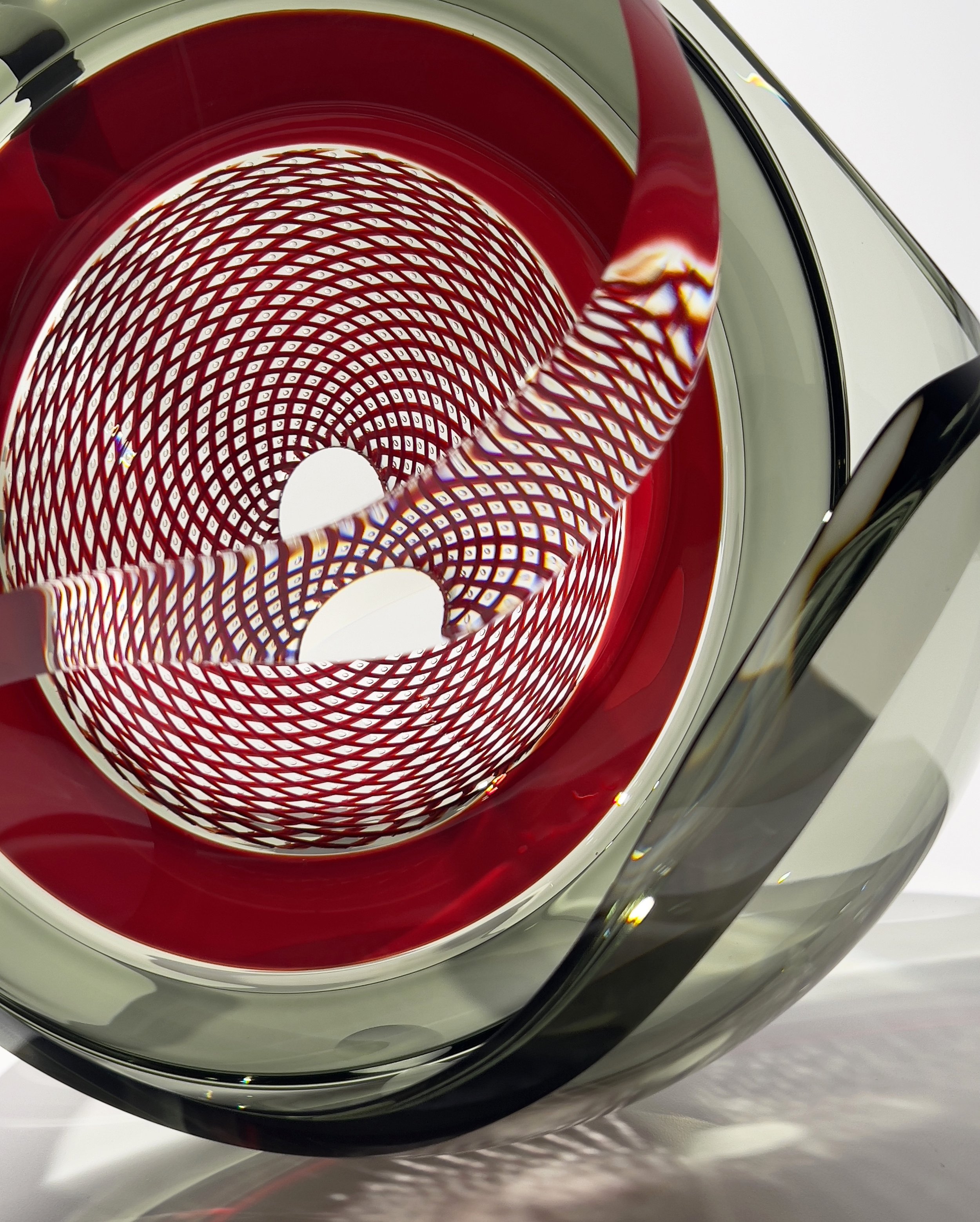

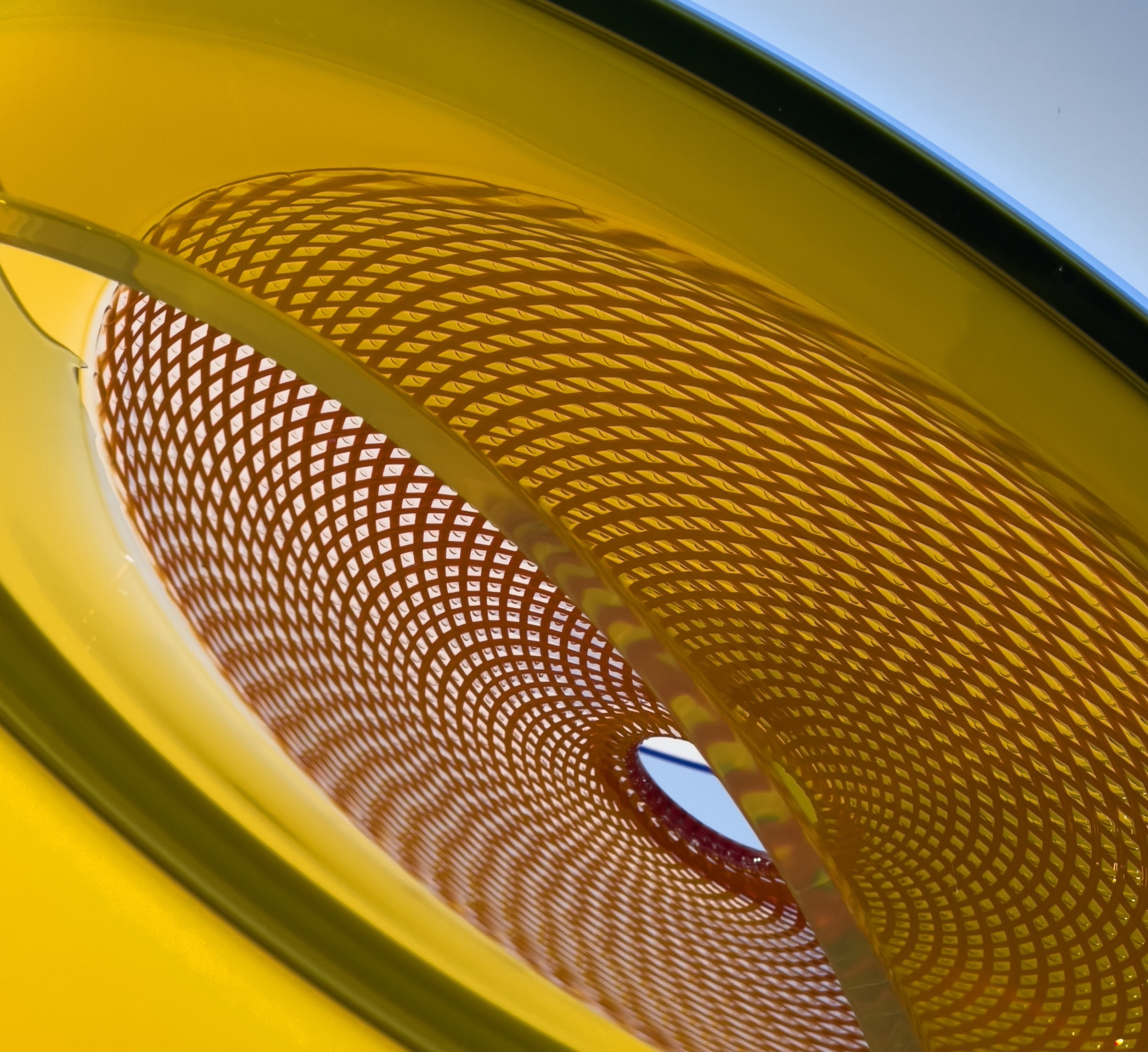

Amber Wave, 2020, detail.

The head of a glassblowing studio is its creative visionary and technical director but being a successful hot-glass artist does not happen in isolation. To actualize an elaborate work of glass art, a group of incredibly talented individuals work together in very close quarters. The master conducts a choreographed whirlwind of intensity, heat, and drama, and with the right assembly of personalities the process can be a lot of fun. Sometimes two artists come together in this dance of effort and joy, not as leader and assistant but as true partners. Though there was a time years ago when Marioni was the boss and Kiley the apprentice, the current collaboration between them is genuinely synergistic—two friends coming together to have a good time in the hot shop, each of whom bring to the experience distinct aesthetics and aptitude. The singular and exceptional results of the venture are a testament to the spirit of skill, spontaneity, experimentation, and friendship that began “way back” and continues to this day.

_____________________________

View the works at the gallery.

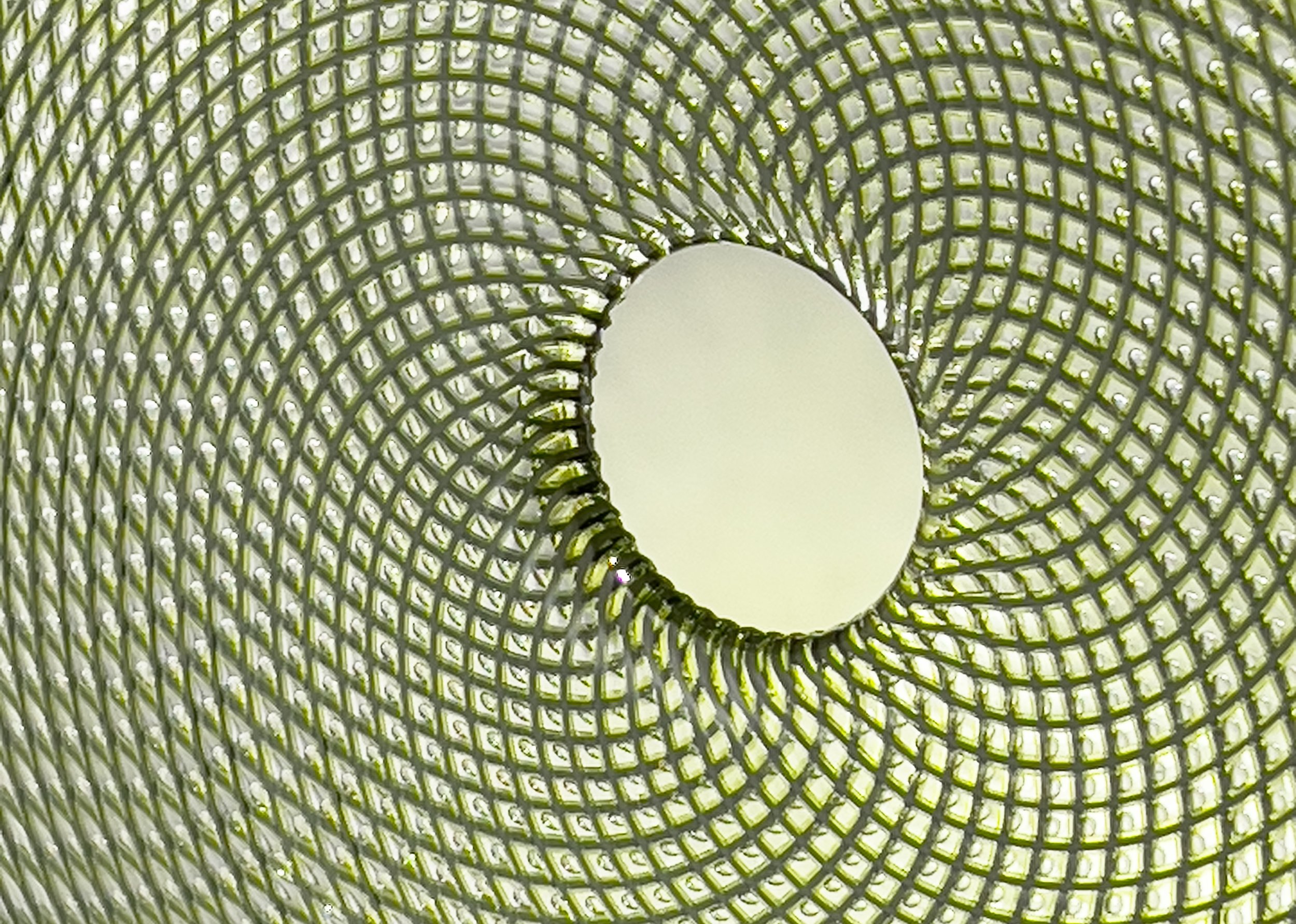

Cresting Reticello, (detail)