no risk, no reward…

David Huchthausen embodies the figure of speech “no risk, no reward.” He doggedly preservers in everything he does, driven by an internal motivation to explore, learn, invent, push. From an early age, he wanted to figure things out, work hard, and pursue his passions. His artwork, which references his interests in architecture, astronomy, history, and the curiosities of humanity and the spirit, is a deliberately enigmatic invitation into a universe of ever-shifting perspectives and synergetic forces.

A wire saw in Huchthausen’s studio.

Huchthausen sees his 50 years in glass in an arc, one thing building upon the next. His first love was architecture, but early on he predicted the waning of the one-man architecture firm and set his sights elsewhere. While a work-study student in the ceramics department at the University of Wisconsin, Wausau, Huchthausen discovered an old glass furnace. He had always been fascinated by glass in architecture, so he blew the dust off the furnace and learned how it worked. Huchthausen knows how to weld, is a good woodworker, and in general subscribes to the philosophy that if you want to know how to do something, you put in the work and figure it out. Soaking up the sparse glass knowledge of those around him, he taught himself the basics. He melted 475 glass marbles developed by Dominic Labino for pulling fiberglass strands, for lack of access to other materials. Soon, he was teaching a night class and selling at fairs. In the early 1970s, he became one of Harvey Littleton’s graduate assistants at University of Wisconsin, Madison, helping to build his first electric furnace, revitalizing equipment, and rebuilding the coldworking shops. Huchthausen has since become a pioneer in coldworking techniques—complex processes that he developed “by the seat of his pants over a long period of time” which suits his hardworking and tenacious disposition. In 1974, at the invitation of glass innovator Joel Myers, Huchthausen went to Illinois State University to finish his MFA then take over their glass program while Myers was on sabbatical. In 1977, he received a Fulbright Scholarship and worked in the J&L Lobmeyr Studios in Vienna. After Vienna, Huchthausen served as Design Director for Milropa Studios in New York and as a university professor in Tennessee.

Huchthausen has been a collector since childhood, and as soon he as could he started accumulating. He acquired copious amounts of material—like Vitrolite (a commercially-produced glass made as an inexpensive substitute for stone in architectural facades), grid glass made by the Corning factory in the 1930s for fluorescent light diffusing screens, palettes of C-grade stock from Schott Optical, and three tons of thick black glass tabletops from an Art Deco restaurant in the Buffalo, NY train station. The sculptures he makes today, often using a dozen types of glass, are a history lesson and homage to the variety of glass produced over the past 80 years. His love of architecture and collecting led him to purchase, among other buildings in Seattle, the extraordinary 150,000 square-foot Bemis Brothers Bag Building, which he redeveloped into artists’ lofts, office, manufacturing, and warehouse space. His two-story loft there is a visual panoply of 20th century decorative arts and glass items that fascinate and influence him. He is also drawn to primitive sculptures, ritualistic objects that embody a spiritual realm he feels complements the metaphysical space of his own, technologically modern, hard-edged glass art.

….the final polish of an Asteroid Sphere in the studio.

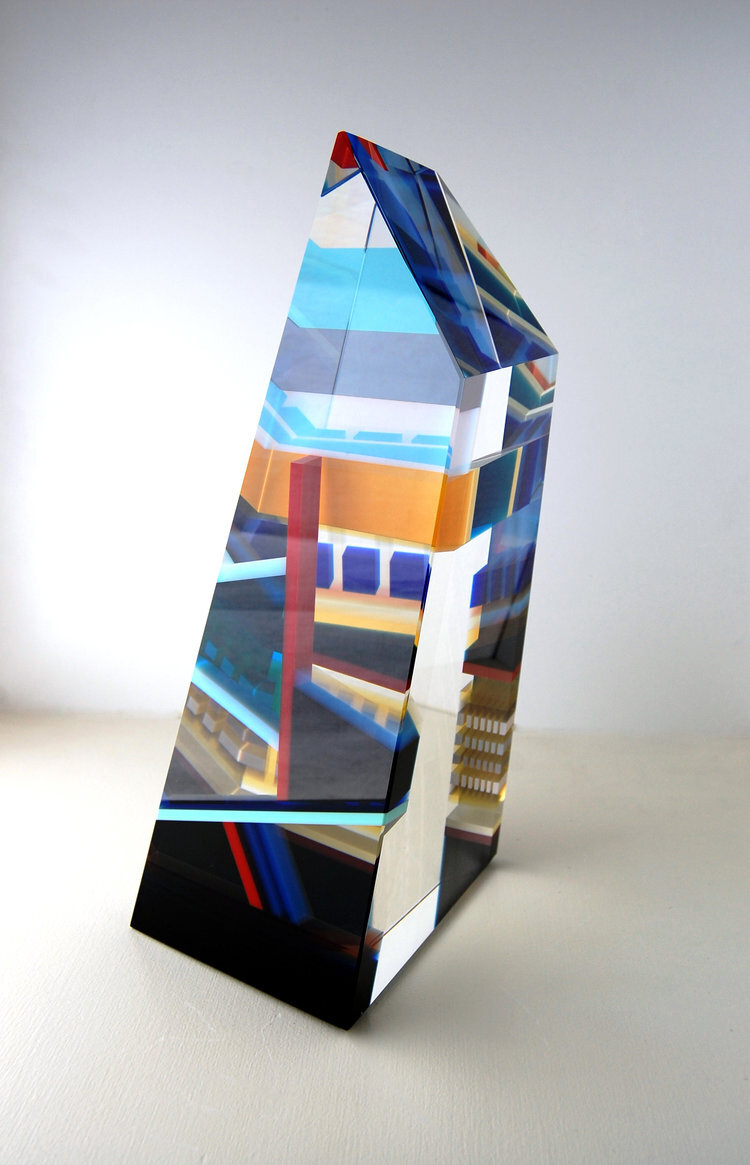

Even during the pandemic, in a large studio about one mile south of his loft, Huchthausen and his assistants continued their tag team operation, devoting countless hours to individual pieces. To begin the labor-intensive process, colored glass fragments are thoughtfully arranged then placed atop or within carved optical glass. Through careful lamination—then repeated cutting, sawing, machining, polishing, buffing, and curing— pristine and riveting sculptures slowly emerge. Light rays passing through the fractures and lenses of the sculpture are halted and redirected. Embedded color patterns either bend in hard-edged distortions inside the sculpture or reflect in diaphanous pools of color around it.

Kristin Elliot working at Huchthausen’s Studio.

In 2019, Huchthausen’s long-time studio manager, Kristin Elliot, moved to Tacoma to set up her own studio. A recent hire, Nathaniel Gauthier (who turned out to be great), took over the position. Both to facilitate Nathaniel’s training, and in sensitivity to the economic turndown during the pandemic, Huchthausen chose to create smaller works at a more accessible price point. Enter the Asteroid series, a fully volumetric, 360-degree experience of visual transformation unfolding as the viewer moves around or shifts the piece. While these works resonate visually and metaphorically with the infinite expanse of outer space, at certain angles the inner reflections take the form or architectural elements such as stairs and windows (a nod to Huchthausen’s background), as though the viewer is traveling both beyond and within.

A few years ago, Huchthausen acquiesced to the persistent encouragement of Susan Warner (then Director of the Museum of Glass in Tacoma) to do a residency in their hotshop. There, and later in the studio in with works such as Stardust Reliquary and Birth of a Star, he experimented with combining cast and blown pieces, embedding spheres, and adding figures cut from Spectrum sheet glass to the surface (a full-circle orbit back to his early Fantasy Vessels, in which thick glass forms were decorated with layers of abstract landscapes, and floating figures cast shadows onto the backgrounds). According to Scientific American, “A star is born when atoms of light elements are squeezed under enough pressure for their nuclei to undergo fusion. All stars are the result of a balance of forces … As long as the inward force of gravity and the outward force generated by the fusion reactions are equal, the star remains stable.” It is an apt metaphor for the work and life of David Huchthausen, who balances the historic with the cutting-edge, the ethereal with the material, vibrant color with translucence and clarity, physical labor with the joyful respite of vintage cars, old wooden boats, and trips to the Philippines (where he owns a small resort). Lastly, there is the balance of control over the creative process with the release of sharing the work. Huchthausen has said:

“Creation is a continual and evolutionary process, constantly digesting and reevaluating past experiences and current perspectives … I constantly strive to generate a strange and curious quality that both tantalizes and challenges the viewer to develop his own response system. The work must have an existence of its own to have any real significance.”

David Huchthausen’s Echo Chambers

This 2004 PBS DVD shows the technical details of David’s sculptural process. Craig Sawchuck Productions.

Available Work by David Huchthausen…

About the Artist…

David Huchthause in his studio. M Stubblefield photo.

David Huchthausen was one of the first artists of the Studio Glass Movement to emphasize cold working fabrication techniques such as cutting, sawing, laminating, and optical polishing. Within his crystal-clear geometric forms, Huchthausen integrates complex shapes, concave lenses and intricate color panels, refracting light as it hits the shapes and reflecting colored glass patterns in the fractures and lenses below and around them. The colored glass patterns occasionally include dichroic glass, a composite non-translucent product made by stacking layers of glass with micro-layers of metals and oxides which, depending on the angle at which they are viewed, can cause an array of colors to display. Huchthausen’s sculptural narrative has always been enigmatic by design, challenging the viewer with its curious and unknowable quality.

With hundreds of one-man and group exhibitions on his resume, Huchthausen is considered a leader in the field. His work is represented in over 75 public collections, including: The Corning Museum(NY); The Chrysler Museum of Art (Norfolk, VA); The Detroit Institute of Arts (MI); The High Museum(Atlanta, GA); The Hokkaido Museum (Sapporo, Japan); The Los Angeles County Museum (CA); The Metropolitan Museum (New York, NY); The Museum of Fine Art (Dusseldorf, Germany); The Museum of Fine Arts (Lausanne, Switzerland); La Musée de Verre (Liège, Belgium); The Smithsonian Institution (Washington, D.C.); The Tacoma Art Museum (WA); and many more.